Toronto Environmental Alliance

February 2, 2015

Speaker:

Franz Hartmann,

Executive Director of the Toronto Environmental Alliance (TEA), an organization with over 50,000 supporters

The Good News

In June 2014, we asked candidates running for City Council to commit to a set of environmental actions we call the Green Action Agenda. In this budget, we were looking for new money for key actions: specifically, improving TTC services and improving Toronto’s vitally important tree canopy. We are happy to see new funding for these important environmental services.

The Not So Good News

However, there are problems with this budget.

There is no new investment in better educating people about waste diversion. Without more money to teach people about what goes in the Blue and Green Bins, Torontonians will continue throwing precious items into the garbage and clogging up our landfill. That is bad for the environment and means our landfill fills up faster than it needs to, adding major new costs in the future.

Another example of not helping people reduce pollution is the TTC fare increase in this budget. A fare increase penalizes the very people who do the right thing by getting them to pay more almost 4% more for helping reduce traffic congestion and cleaning the air.

We are told raising property taxes above the rate of inflation is a nonstarter, after years and years of property tax increases that are at or below the rate of inflation.

So why is it that raising TTC fares annually above the rate of inflation is okay?

If a fare freeze is off the table, then I ask City Council to treat those who use the TTC the same way as other Torontonians are treated. Either limit the fare increase to 2.25% or raise property taxes to 3.7%. One way or another, stop penalizing people for doing the right thing and using the Better Way.

Ironically, while this budget doesn’t help people reduce pollution, it does encourage some companies to pollute. Right now, companies that discharge wastewater into our sewer system do not have to pay the city the full cost of cleaning up the pollution. Every year, city ratepayers pay $3 million extra, the difference between what companies pay and what the city pays.

Councillor Layton has moved a motion that would stop this bad environmental practice. We urge all Councillors to support this.

The Bad News

Finally, this budget remains virtually silent on getting the city ready for climate change.

There is no new money to research, plan and implement the many, many programs Torontonians need to prepare for the biggest threat facing the planet. We are told there is no money because property taxes have to stay at 2.25%.

Many seem to think climate change is a future cost we can ignore. They are wrong. We are already paying for climate change and the cost makes a 2.25% property tax increase look like loose change.

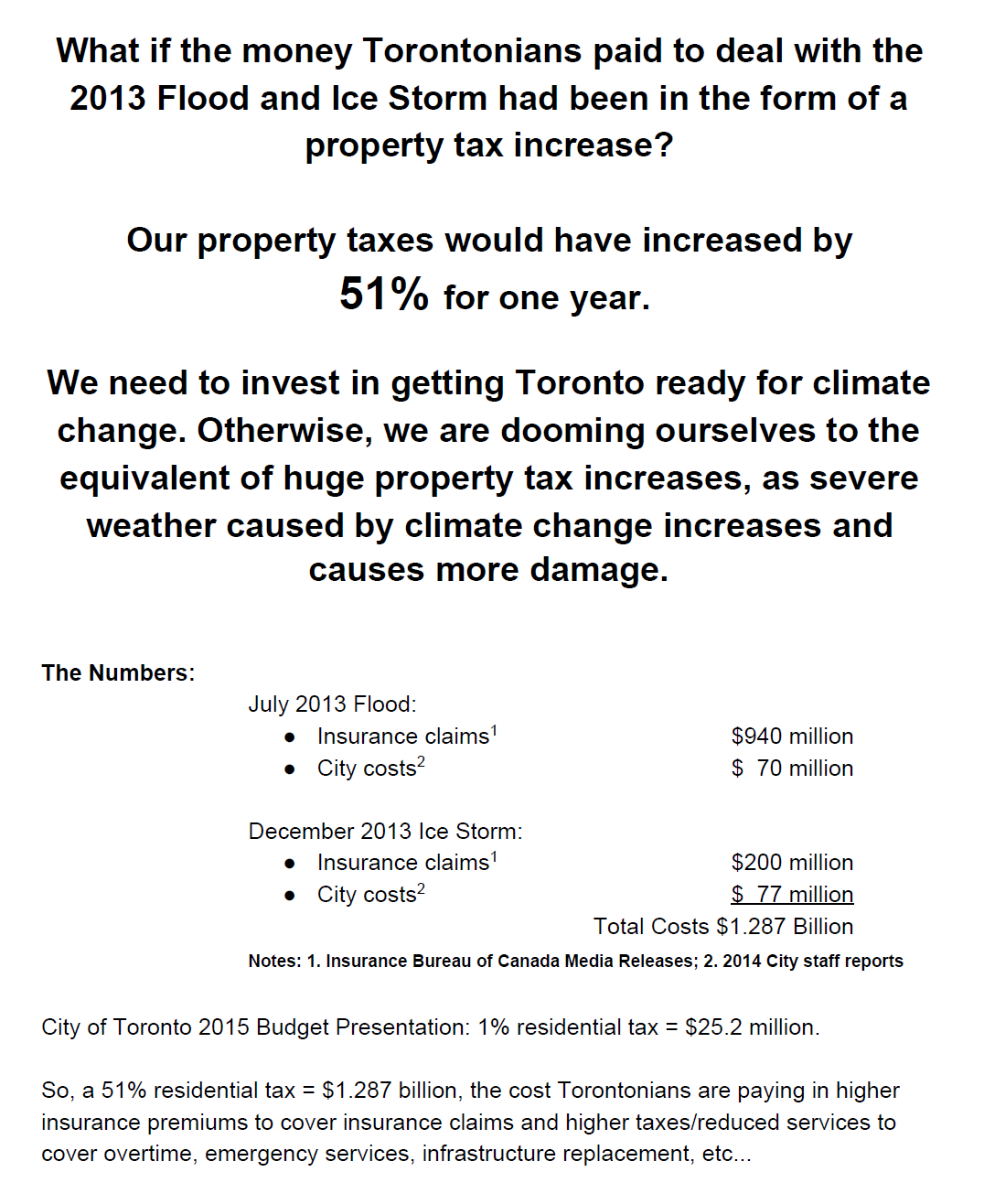

I want you to think about what would happen if you proposed a one-time 51% tax increase to Toronto residents. Using the city’s calculation, this would raise about $1.3 billion. City Councillors would never agree to this.

But this is exactly what Torontonians paid to deal with the big flood in July 2013 and the ice storm in December -- the equivalent of a 51% tax increase, or $1.3 billion:

- $1.14 Billion in insurance claims, which we will all pay in higher insurance premiums

- $147 million in government costs for overtime, replacing equipment, emergency services, etc. -- costs paid for by provincial and city taxes

This figure doesn’t even include the deductibles people paid when they made insurance claims.

City Council is quibbling about a 2.5% property tax increase. Meanwhile, the two storms of 2013 actually cost us the equivalent of a 51% property tax increase and this budget is doing almost nothing to stop this from happening again even though the scientific evidence suggests we will see more severe storms causing more property damage.

Council has two options:

1. Keep property taxes low and do nothing to prepare the city for climate change and doom Torontonians to pay huge costs, equivalent to the 51% tax increase they paid in 2013.

2. Or, increase property taxes to invest in the programs, technologies and bylaws that get Toronto ready for climate change.

Option 2 won’t be cheap. But it will be the bargain of the century compared to Option 1.

How can I get you to support Option 2? Get informed about the true costs of inaction.

Be financially prudent, spend the next year learning what climate change is costing and will cost the city. Then, in 2016, you can adopt a budget that helps us avoid the huge financial liability that inaction on climate change will bring.

For more information, contact:

Franz Hartzmann

Toronto Environmental Alliance (TEA)

416-596-0660